A Brief History of Windows

The first windows were not windows at all; mere wounds hacked into clay or stone that ceded a ration of air and a thread of weather. These crude openings were made for breath, not beauty. Around the third millennium BCE, in the dry heat of ancient Egypt, thin sheets of alabaster were fitted into Old Kingdom temple walls to allow honeyed light to filter through onto the carved reliefs and painted walls. Later, in Classical Greece and Imperial Rome, builders experimented with lattices, shutters, and thin panes of horn in attempts to admit the world without surrendering to it.

By the first century CE, the furnaces of Alexandria had learned to cast and polish glass to be used in villas and bathhouses. Their glass was green, bubbled, and dense, but shimmering with intention. A few fragile sheets have survived, and they serve as the earliest examples of our desire to trap the sky.

Light retreated after the fall of Rome. Across the ruins of its empire, the early Middle Ages built for endurance rather than illumination: monasteries, citadels, and motte-and-bailey castles that soon learned the permanence of stone. The window narrowed to a slit — a bowman’s eye — shaped for defence, not delight. By the high medieval period, thick curtain walls and towers of grey limestone carved daylight into thin blades of necessity. It was an age of divided kingdoms and uneasy faith, when power was measured by how much darkness a fortress could withstand. Yet even behind those walls of vigilance lingered a quiet yearning for the world beyond — a glimpse of light and a breath of sky.

Caernarfon Castle in Wales

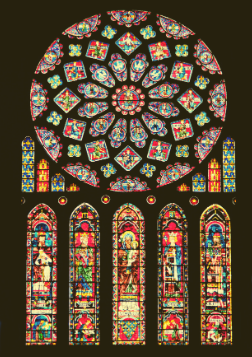

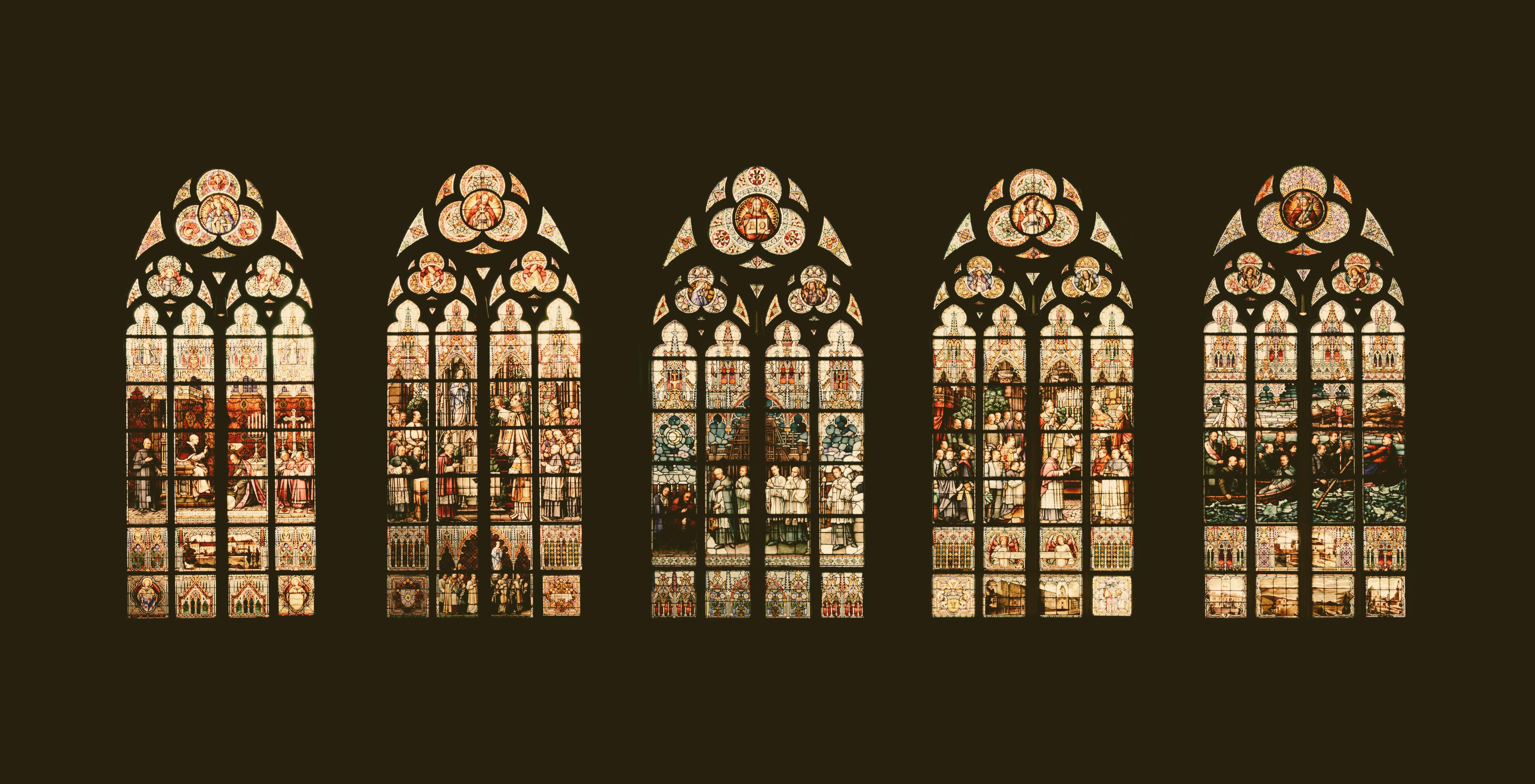

As the Middle Ages matured and trade, learning, and monarchy revived, the horizon softened. Castles gradually grew less severe in their design and outlook, their interiors ornamented with tapestries and windows of glass no larger than coins. The Gothic imagination, born in the twelfth century, lifted stone into light. Vaults arched skyward, tracery blossomed across windows, and coloured glass turned scripture into colour. The rose windows of Chartres and Canterbury declared that to look towards the light was to believe. Saints, kings, and genealogies of faith blazed from high through fragments of colour. Nowhere did walls dissolve so completely as in the Sainte-Chapelle of Paris (1248), where glass replaced masonry altogether and daylight itself became the building’s structure. Light had been tamed.

The Saint-Chapelle is a royal chapel in the Gothic style, within the medieval Palais de la Cite, the residence of the kings of France until the 14th century.

Elsewhere, other civilisations shaped light differently. In the Islamic world, geometry replaced figuration, and light became pattern. The palaces of Moorish Spain, the Alhambra in Granada being a fine example, transformed sunlight into ornament. Its latticed arches and muqarnas ceilings scattered radiance into tessellated wonder. Around the same time in China, timber-framed houses were fitted with paper windows that diffused light, decorating spaces with intimacy and calm reflection rather than bedazzlement. In Japan, paper latticed shōji screens filtered light into rooms designed for restraint and clarity that celebrated a geometry of privacy rather than spectacle. Each culture sought the same balance between revelation and restraint, between the promise of the outside and the privacy of the interior, widening the aperture a little more, allowing not only light but curiosity to enter.

The Renaissance gave the window new meaning. In 1435, the Florentine humanist Leon Battista Alberti, in his Latin treatise De Pictura, compared painting to “an open window onto the world,” suggesting that to frame something is to understand it. The window became a metaphor for perspective itself: a disciplined way of seeing. Humanism and geometry met at the threshold, and the world, at last, appeared ordered.

From fortress to façade, the window has mirrored our confidence and our fear. Each age has built the windows it deserves, and each has found itself reflected there. We have contorted them, embellished them, and trusted them to hold the world at bay. Now we live almost entirely through them.

Strictly, a window belongs to architecture. It is a measured opening to the world. Yet any pane that mediates vision behaves like one. The aquarium, the display case, and the screen all continue to repurpose transparency into meaning.

On Painting Leon Battista Alberti

The Transparent Threshold

A window is a paradox. It is an illusion of access that reaffirms separation. It is honesty disguised as openness. We live surrounded by literal, digital, and mental windows, each claiming to connect us to the outside while quietly containing us within. Or vice versa. Alberti’s metaphor was prescient — the painting, like the window, instructs us in seeing but also in forgetting. Through the frame, we learn not only what the world looks like, but what it should look like, a composed, coherent, and proportioned place.

Light moves across the pane with its own language of glares, shadows, and reflections. Even when we think we are looking through glass, we are looking with it. The philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty wrote that perception is not the act of a detached observer but a meeting of bodies and the world. The window, then, is not neutrality, but the negotiation of a fragile contract between inner and outer.

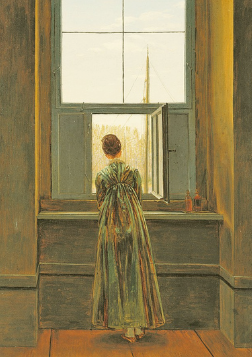

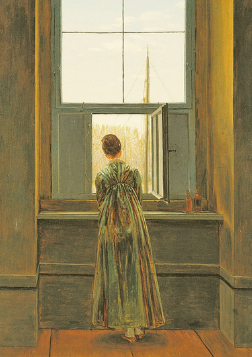

That negotiation is not purely visual; it is also emotional. The window informs not only how we see, but how we feel. Through glass, emotion becomes visible. It becomes concentrated, legible, and cinematic.

The emotion, however, is real. Windows, even those that trick or serve as mere decoration, are outlooks that reflect and convince us of our emotions. On our screens, windows are instruments of empathy, emblems of solitude, and portals of longing, though that longing is rarely still.

Every act of looking carries a desire to move. Longing leans outward, searching for somewhere to go. The eye travels before the body does. Perhaps that is why we associate windows with departure. On screen, we are familiar with the image of the watcher left behind, and the face framed by glass as the train pulls away. The desire to see beyond becomes the desire to be beyond. From the carriage window or the aeroplane porthole, the world scrolls past like a silent film. Distance turns to narrative, reflection to rhythm. We mistake motion for meaning, but perhaps that is the window’s final lesson: to see is always to move, and every act of looking carries us somewhere else.

The window’s history is, after all, a history of movement, from shadow into light and from enclosure into expression. It is where stillness begins to travel.

The House of Light

Across faiths and centuries, the same theology of light endures. In Shiraz, Iran, the Nasir al-Mulk Mosque washes its walls with colour each dawn through a stained-glass sunrise that turns architecture into devotion. The window mediates between radiance and restraint, revealing what cannot be looked at directly. Divinity is made visible.

Centuries later, painters like Johannes Vermeer found revelation in the light that fell through household windows. In works such as The Milkmaid (c. 1658-60) and Woman Holding a Balance (1662-63), the sacred lingers in quiet domesticity, falling on figures absorbed in stillness.

Woman Holding a Balance (1662-63), Johannes Vermeer

Beginning in the 1960s, the American artist James Turrell turned from painting to light itself, treating perception as an architectural material. His early experiments in Los Angeles explored how openings, corners, and apertures could shape the very experience of seeing. In his later Skyspaces (from the 1970s onwards), the window returned in its most elemental form — a void cut into the ceiling through which the sky becomes a living canvas. At dawn or dusk, the room itself seems to pray. The architecture dissolves, and the act of looking becomes its own kind of devotion.

The Rothko Chapel (1971) in Houston evokes a similar stillness. Conceived by the Russian-American painter Mark Rothko, the octagonal, windowless building holds fourteen vast canvases of deep purples and near-black hues. The absence of literal windows makes the paintings themselves behave like thresholds that absorb rather than reflect light. The austere simplicity of the ecumenical room is lifted by diffused light and paintings that seem to gently pulse with the viewers’ interior weather of feeling.

Light remains our oldest metaphor for understanding, and the window its chosen instrument, yet in time, light would be managed rather than worshipped. It would be measured, displayed, and preserved behind glass.

Bodies Behind Glass

The display case, the aquarium, and the glass coffin are windows that refuse their own promise. They offer vision without access and intimacy without air. They are panes that face inward, designed not to release but to contain.

The aquarium scene in Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet captures the romantic notion of recognition through obstruction. Romeo’s eyes meet Juliet’s through water and glass. Their faces waver and are half-veiled by the slow drift of fish whose indifference deepens the moment’s fragility. It is a perfect metaphor for a love refracted by circumstance. What joins them is not contact but attention. The pane both divides and consecrates, and their love begins as the art of seeing through something.

In Amsterdam’s red-light district, the window is stripped of tenderness. Light saturates the body, the body attracts the gaze, and transaction replaces innocence. Desire stands contained, safe, and commodified. Yet the difference between the lovers and the workers is not moral but economic and depends on the same grammar of distance. In love, as in commerce, the glass confers value. What we cannot reach becomes what we most desire.

Vladimir Lenin’s body lies beneath glass in the Mausoleum on Red Square. It rests in a crystal sarcophagus lit from below, skin preserved by chemical precision, and re-embalmed each year in a laboratory devoted to his permanence. The effect is both devotional and forensic. It is a shrine, specimen, and faith embalmed in science. The glass denies decay but not morbidity, keeping ideology in view while removing it from life. For more than a century, visitors have queued to look upon Lenin — a relic of political immortality. The body represents both the triumph and the exhaustion of belief: a revolution fixed forever in its own amber.

Even the Mona Lisa now dwells behind her own glass altar. The pane that protects her from the violence of admiration has become part of her aura. Visitors queue as if approaching a relic, their phones lifted like votive candles. What they photograph is not the painting but its condition of preservation, and the gleam that separates them from her. The glass, not the portrait, is the true object of worship.

The museum inherited this logic. From the sixteenth-century Wunderkammer — those private “cabinets of curiosity” that gathered shells, bones, maps, and relics under glass — to the modern vitrine, display became a system of knowledge. Wonder was no longer spontaneous; it was organised. Glass made amazement measurable. The act of encasing turned fascination into a method, a way of asserting that value could be seen, not merely felt.

Cabinet of Curiosities (1690s), Domenico Remps

The cabinet, the vitrine, and the climate-controlled box are our secular reliquaries. Museums promise preservation, but their true power lies in distance. Wonder depends on separation, and value on enclosure. If cathedrals turned light into faith, museums have turned it into evidence. The artefact, the relic, and the masterpiece all exist under the authority of glass. To see something encased is to believe it has worth. The window has become the certificate of reality itself.

And we repeat the ritual endlessly. In the digital window of the screen, we curate our own exhibitions: faces filtered, bodies embalmed in pixels, and lives arranged and preserved for the gaze of others.

Glass as Fear and Power

In John Carpenter’s 1978 horror, Halloween, the suburban grid of lit windows, a usually comforting pattern of domestic order, turns treacherous. The killer, Michael Myers, looks in. When the camera lingers on the glass, it is hard to tell which side we are on. Horror’s genius lies in the confusion of believing the window serves to protect us, when in fact, it has already betrayed our location.

If horror finds danger in domestic transparency, modern architecture monumentalises it. The skyscraper was built to see and to be seen. It commands the skyline while concealing those inside. The glass towers of the mid-twentieth century — Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building (1958) or New York’s Lever House (1952) — perfected this aesthetic of moralised transparency, structure as spectacle, and openness as virtue. Glass became the twentieth century’s favourite moral, something clean, open, and rational. But transparency is not innocence; it is control. Behind the mirrored façades of financial districts, reflection replaces vision. The city becomes a hall of self-regard, each surface echoing another until depth disappears. At night, the towers glow like lanterns of isolation, emblems of an openness that conceals its own surveillance, monuments to the illusion of trust.

The faith in visibility finds its most literal expression in the glass bridge. Tourists walk upon the void, the earth hundreds of metres below, the abyss made visible. These transparent walkways promise courage through exposure: the thrill of safety that feels like danger. The windows to the ground reveal what sustains you and what could swallow you. The experience is philosophical as much as physical. It is a rehearsal for mortality. To walk on glass is to test the limits of faith in the unseen strength beneath our feet.

Zhangjiajie Glass Bridge, China

Our cities, our screens, and our bridges all share the same creed. They assure us that openness equals virtue, and that visibility guarantees honesty. Yet glass has always known another truth: that every act of seeing can turn to spectacle, and every promise of light hides its own vertigo.

Reflections and Revelations

As evening gathers, the world reverses. The window that once opened outward now turns inward. The exterior fades into darkness, and our own reflection rises on the surface. We become half ghost and half witness. We stand before the glass and see not the outside world but the self, caught between exposure and retreat. Every window ends as a mirror.

In domestic quiet, this moment can be tender — a lamp behind us, the soft hum of a room, the suggestion of privacy — but the reflection carries unease. We are confronted by the image of ourselves. The face that has spent the day translating light into comprehension now requires our attention. Behind us, the interior glows; beyond us, the night waits. The window holds both, refusing to choose.

Writers have always understood this duality. Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse unfolds around the movement of light across rooms and water, the slow merging of perception and memory. For Gaston Bachelard, the window was “the house’s eye,” the point where daydream becomes architecture. For both, glass mediates consciousness itself. It is the fragile border where thought meets world.

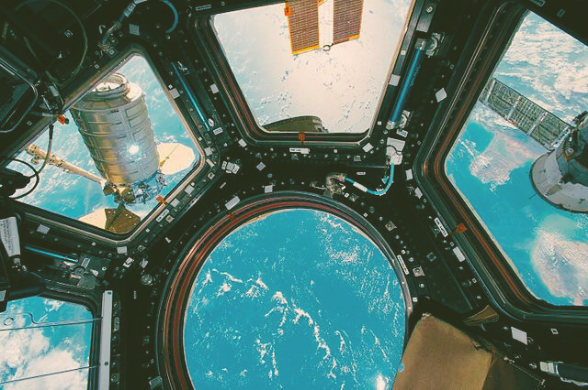

Far from the domestic, astronauts describe something similar when they speak of the Cupola on the International Space Station, the domed window that faces Earth. Through it, they experience what they call the overview effect: a sudden collapse of scale, the realisation that everything — land, weather, war, language — fits within one luminous sphere. The window at the edge of the cosmos becomes the final mirror, returning to us the smallness we forget.

We live in an age of infinite panes, from our screens to our towers, that repeat the same longing for a world that might look back. Perhaps, in reflection, it does.

From the domestic to the cosmic, glass has carried the same lesson: transparency is never empty. Every reflection stores the memory of those who have looked through it. Every pane is a ledger of gazes, layered like fossils. The world has been observing itself through glass for millennia, rehearsing the slow art of recognition.

To the Lighthouse Virginia Woolf

Every Window is a Promise

Perhaps this is why we keep building them. Every window repeats the same quiet faith, the sense that distance need not mean loss and that what lies beyond can still be reached through light. The material may change — stone to lead, steel to pixel — but the gesture endures. We press our faces to the pane, searching for confirmation that the world continues beyond our touch.

We trust glass to bear our longing. We trust it to hold against weather, time, and grief. In the end, a window is not just a frame for looking; it is a frame for hope — an architecture of seeing that keeps belief alive.

Outside, rain resumes its slow work, tracing the same faint hieroglyphs it has written for centuries. Inside, the pane glows softly, reflecting everything that has ever stood before it.

Some of the links in this article are affiliate links. If you buy through them, Yellow Agora may earn a small commission — at no extra cost to you.