A Fractured World

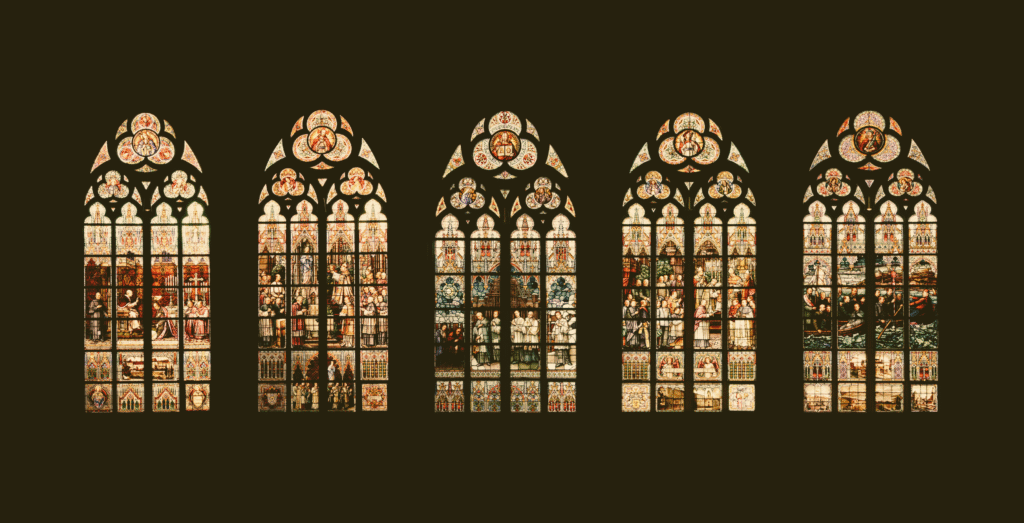

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne was born in 1533, near Bordeaux, into a France torn between Catholicism and Protestantism. The Reformation, a movement that had begun with Martin Luther’s challenge to the authority of Rome, had unstitched Europe’s religious fabric. What started as spiritual renewal soon splintered faith.

Montaigne’s family stood at the centre of this fragile world: Catholic by heritage, tolerant by inclination, rich enough to be envied, and vulnerable enough to be prudent. Their estate, the Château de Montaigne, was both refuge and symbol of social ascent, a house built from trade rather than birthright.

His great-grandfather, Ramon Eyquem, had made a fortune as a herring merchant and bought the estate and the title of Seigneur de Montaigne — Lord of Montaigne — in 1477. The family expanded their activities to the realm of public service and established themselves in the noblesse de robe — the administrative nobility of France. Pierre Eyquem, Montaigne’s father, served as a French Roman Catholic soldier in Italy for a time and later as the mayor of Bordeaux. It was during his time in Italy that he developed the humanist and pedagogical ideas that would shape his son’s life.

Montaigne grew up in contradictions. He was heir to a fortune he neither sought nor understood, and though privileged, the infant Montaigne was sent to live with peasants, to learn humility and simplicity.

“… from the cradle he sent me to be suckled in some poor village of his… he reckoned that I should be brought to look kindly on the man who holds out his hand to me rather than on one who turns his back on me and snubs me. And the reason why he gave me godparents at baptism drawn from people of the most abject poverty was to bind and join me to them.”

“Of the Education of Children” (Book I, Chapter 26)

Pierre arranged an experimental and ambitious education for his son. Upon returning home, the young Montaigne was spoken to exclusively in Latin, so that he might be steeped in antiquity. His tutors, following the newest humanist ideals, encouraged curiosity, believing it to be the surest path to learning.

From Plutarch, he learned that character is a life traced through its inconsistencies; from Seneca, that philosophy should serve life rather than abstraction; and from Lucretius, that chance and death govern all things, and tranquillity lies in acceptance.

As a young man, he entered the Parlement of Bordeaux, serving as conseiller — a role that required him to summarise cases, appraise conflicting documents, and to build sense from dispute. The habit of fairness became a habit of mind. He learned early that the truth of one party does not cancel the truth of another.

The Solitude of Conversation

Montaigne’s public career might have continued without incident, had he not met the poet, thinker, and his mirror in intellect and spirit, Étienne de La Boétie. Their friendship was a union so complete that Montaigne struggled to define it: “If you press me to tell why I loved him, I can say no more than because it was he, because it was I.”

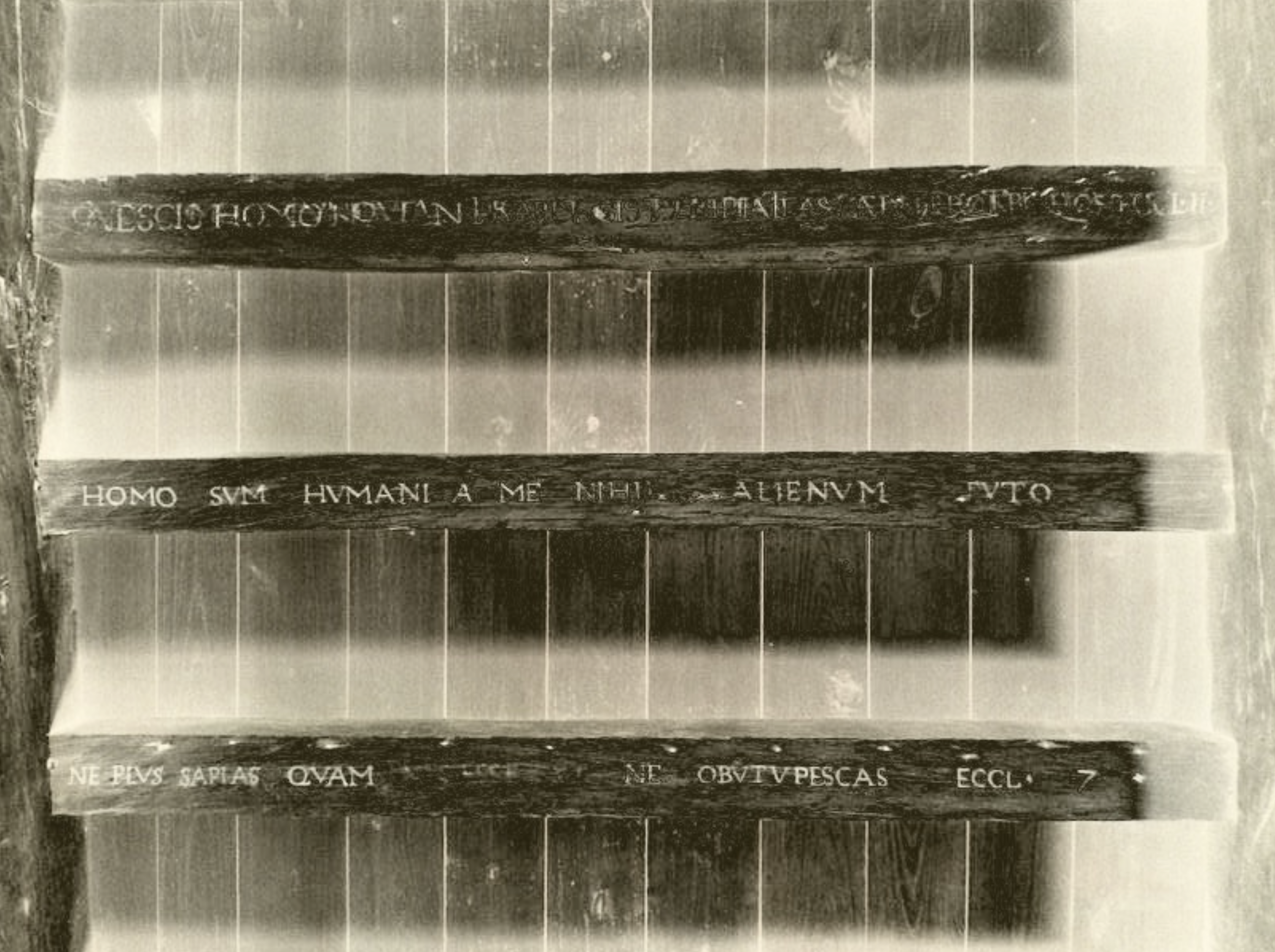

When La Boétie died of the plague in 1563, Montaigne was unmoored. He withdrew from politics, closed his door to the world, and built a tower. On its upper floor he created an extensive library, its beams etched with Stoic and Epicurean maxims to remind him to live calmly, think clearly, and die without fear. There he read, annotated, and began to write the first of his Essais, or Attempts, which may be thought of as small experiments of thought.

He could, of course, afford this retreat. His wealth allowed him to turn leisure into labour, but it was grief that made the work necessary. The essays became a continuation of the conversation he had lost. They were, in one sense, solitary: reflections written in the absence of a voice; yet, in another, they were profoundly social. “We find ourselves only through the reflection of others.”

The idea, that identity exists between, not within, shaped everything that followed. The self, for Montaigne, was not a monument but a mirror. He knew that we do not come to know ourselves alone, but that we see ourselves refracted through friendship, through error, and through the gaze of others. His was a philosophy of reflection, not revelation. It was an understanding that knowledge is born in relation.

Les Essais

Montaigne’s essays are written as one thinks: they digress, contradict, circle, and revise. “If my mind could gain a firm footing,” he admits, “I would not make essays, I would make decisions.”

He does not depict being but passing. His pages, like weather fronts, move with constant changes in pressure, temperature, and wind rather than argument. To read him is to observe a consciousness discovering itself by writing. The essay becomes the shape of the mind in motion: knowledge not as possession but as exploration.

Portrait of Michel de Montaigne (1570s) artist unknown

His essays are often substantiated by ancient Greek and Roman history, Stoic philosophy, poetry, and myth, whilst also being autobiographical, domestic, and frank, filled with recollections of illness, friendship, appetite, and fear. He could move from Alexander the Great to his cat, from Cicero to his kidney stones, with no loss of dignity or insight. That mixture of erudition and candour gives his writing its enduring freshness.

Nowhere is his method more revealing than in Of Cannibals. Here, the essay becomes a kind of moral inquiry into the limits of his own civilisation’s certainty. He describes the Tupinambá people of Brazil, some of whom had been brought to France. Where the courtiers saw only barbarism, Montaigne saw the mirror image of Europe’s own cruelty.

“… every man calls barbarous anything he is not accustomed to… Those ‘savages’ are only wild in the sense that we call fruits wild when they are produced by Nature in her ordinary course: whereas it is fruit which we have artificially perverted and misled from the common order which we ought to call savage. It is in the first kind that we find their true, vigorous, living, most natural and most useful properties and virtues, which we have bastardized in the other kind by merely adapting them to our corrupt tastes.”

“Of Cannibals” (Book I, Chapter 31)

His tolerance was radical because it humanised truth. For Montaigne, understanding others was another form of self-knowledge. The barbarian becomes the question we dare not ask of ourselves.

The magisterial role that taught him judicial patience became ethical grace in his thinking. “It is putting a very high value on one’s conjectures to have a man roasted alive because of them.” He saw that cruelty was the child of certainty and that mercy began in doubt.

Montaigne’s Wheel

Montaigne’s thoughts turn upon themselves like a wheel in motion. Each essay revises the last, and each discovery carries the seed of contradiction. Truth, for him, was not a point of arrival but a never-ending return that kept the mind alive.

“To judge appearances that we receive from subjects, we would need a judicatory instrument; to verify that instrument, we would need a demonstration; to verify the demonstration, an instrument; here we are going round in a circle. Since the senses cannot stop our dispute, being themselves full of uncertainty, it must be up to reason; no reason can be established without another reason: here we are regressing to infinity.”

“Apology for Raymond Sebond” (Book II, Chapter 12)

Montaigne wrote those lines while composing his Apology for Raymond Sebond, an essay that began as an act of filial loyalty. His father, who admired Raymond Sebond’s Theologia Naturalis, had asked him to translate the work into French so that those not versed in Latin might read it. Sebond had argued that divine truth could be proved by reason through the study of nature. Years later, when theologians and reformers began attacking the book as impious, Montaigne took up his pen to defend it.

However, in attempting to prove the strength of reason, Montaigne exposed its weakness. Every argument for certainty led back to doubt: if our senses are unreliable and our reason depends on them, how can we trust any claim to knowledge, sacred or secular? He found that even the effort to prove God’s truth rested on human frailty. The Apology became a work of scepticism, not theology — a confession that reason collapses beneath the weight of its own ambition.

This realisation was not merely philosophical; it was moral and historical. France was bleeding from its Wars of Religion (1562-98), its people divided by creeds that promised certainty and delivered only cruelty. Montaigne saw that the need to be right was destroying the capacity to live. His scepticism, then, was not denial but compassion, and a refusal to let truth become an instrument of violence.

The wheel is both epistemological and existential, revealing the structure of knowing and the condition of being: nothing stands still, not our thoughts, our beliefs, or the world they attempt to grasp. We live within movement, and it is movement that makes life intelligible.

He reflects us as we are: inconsistent, partial, unfinished. Yet he does not drown in his reflection; he converses with it. Each essay is a meeting — with La Boétie, with the ancients, with the reader — and in that meeting, knowledge is made. “Truth and reason are common to all men, and are no more his who spake them first than his who speaks them after.” Knowledge, he believed, arises between minds, not inside them.

This, too, is part of the wheel: the endless exchange of thought, the turning of one intelligence upon another. He looked to his pages for correction. The self, for him, was something one revised.

That belief gives his writing a rare tenderness. He could be vain, inconsistent, self-amused, but never cruel. He doubts himself so that he need not doubt others. In a world that mistook certainty for virtue, Montaigne made humility an act of intellect: a wheel forever turning toward understanding, never completion.

Diplomacy and Travels

During his later years, the “accidental philosopher,” in his own words, was drawn again into public life. Twice he served as mayor of Bordeaux, mediating between Catholic and Protestant factions. His temperance did not go unnoticed. Both Henry III and the future Henry IV — king and challenger, Catholic and Huguenot — trusted him as envoy and counsellor.

Portrait of Michel de Montaigne (circa 1578), attributed to Daniel Dumonstier

At the height of civil war, Montaigne negotiated between them, charged with the diplomacy of survival. His intelligence was luminous but never ostentatious; his brilliance lay in calmness, in the steady courtesy that made enemies listen. In a world of zealots, he was indispensable precisely because he refused zeal.

He travelled widely through Europe, recording in his Journal de Voyage the manners of inns, the posture of horses, and the changing temper of towns. In 1581, he reached Rome, where he was received by Pope Gregory XIII and granted a private audience. He kissed the pontiff’s slippers, as custom required, and presented his Essais for examination by the Vatican censors. They found in them nothing heretical, only a few turns of phrase too free for comfort, and allowed the work to circulate. Even in Rome, amid ceremony and orthodoxy, he remained himself: courteous but unconvinced, respectful yet unpersuaded. His composure was its own quiet heresy.

Lessons for the Divided Present

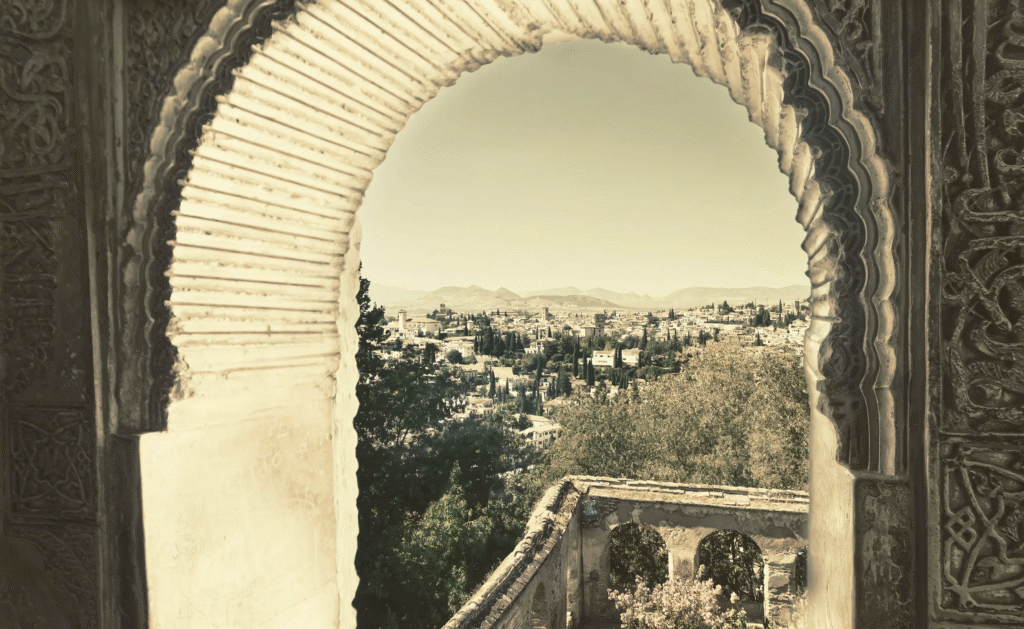

Might Montaigne look upon our digital agora and ask: Have we built towers of reflection or siege?

In an age of conviction, opinion, and seemingly unbound access to knowledge, to admit uncertainty feels indecent. The ease with which we now share and curate our interests, thoughts, identity, and morality has led us to residing in echo chambers, feeding upon reinforcements and self-confirming truths.

Across the West, politics has fractured into tectonic plates of left and right, and the middle ground, once a space of exchange, has thinned to a fault-line. Each camp demands allegiance, and hesitation is treated as betrayal. The language of moderation has fallen out of fashion. Ours is a time of division, of shouting until we are blue, or red, in the face.

Perhaps it has always been so. Sixteenth-century France was no less divided: a country split by faith, where certainties had turned to swords. Yet, amid the turmoil, Michel de Montaigne made a philosophy out of not knowing. His motto, carved into the wooden beams of his tower library, asked the simplest of questions: Que sais-je? — What do I know?

To Montaigne, doubt was strength. He transformed uncertainty from an affliction into an art and offered a way to live honestly within the limits of knowledge. If Montaigne could teach anything to the modern world, it would be this: that doubt is not decay but civility.

The Art of Uncertainty

Montaigne died in 1592, reportedly serene, hearing Mass from his bed. His tower still stands, the carved inscriptions remain, and the quiet rows of books continue to breathe dust and sunlight. It is easy to imagine him there: seated between certainty and doubt, reading and writing himself into being.

His influence ran quietly through later centuries: in Shakespeare’s borrowing of passages, Pascal’s introspection, Emerson’s self-reliance, and Nietzsche’s restless questioning.

What, then, does Montaigne offer us now?

A posture, not a programme. The reminder that thought need not conclude to be complete.

To be confident in uncertainty is not to drift but to dwell attentively in the in-between and to see how little we see and keep looking anyway. The essays teach us that knowledge is a relationship, not a weapon: between self and world, between mind and body, and between one generation and the next.

In a culture of instant opinion, Montaigne’s slowness feels radical. He gives us permission to hesitate, to revise, to live in conversation with doubt. His scepticism is not an absence of belief but a tenderness towards the unknown.

If our world, like his, has moved from unity to fracture, from a brief calm to renewed division, then perhaps his question is the most faithful one we can ask. It is the question that keeps thought human, and humanity humble:

What do I know?