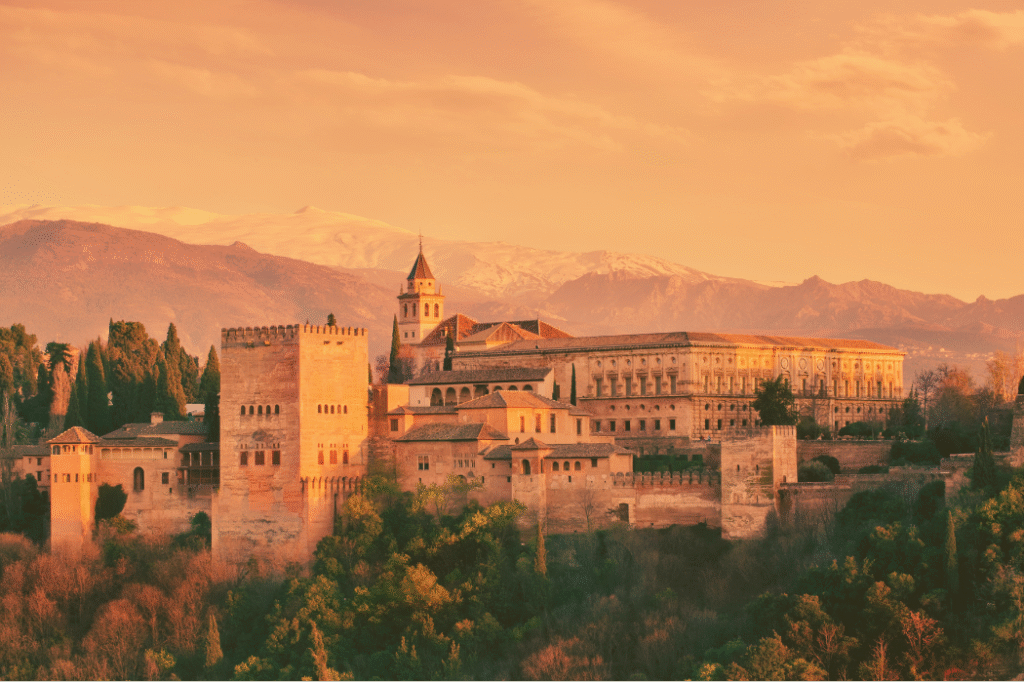

Located in the Spanish region of Andalusia, Granada is a city that lives in layers. At its heart, the Darro river runs in a narrow channel, spanned by ancient bridges and lined with remnants of those destroyed in the eighteenth century, when the construction of the Plaza Nueva reshaped the riverbank. The river’s name originates from the Latin word aurum — ‘gold’ — recalling the gold panners who once sifted its waters. On one side, the medieval Albaicín winds upward in a tangle of streets, whitewashed houses, and hidden courtyards. On the other, the modern city unfurls toward the plains. And above it all, fixed on its own red hill, stands the Alhambra: fortress and palace, sentinel and dream.

A City of Thresholds

Granada has always been a place of crossing. Iberian tribes settled here, Romans laid roads through it, binding it into their empire, and the Visigoths claimed it before the Moors established al-Andalus. For centuries it stood as a frontier city — a threshold between north and south, between Christian and Muslim realms. Merchants and travellers passed through as well, using Granada as a waypoint between the plains and the Mediterranean, between the interior of Iberia and the Maghreb beyond the sea. It became the jewel of al-Andalus, the last stronghold of Muslim Spain, a place where art, science, and poetry flourished even as the rest of the peninsula fell to Christian kingdoms.

By the fourteenth century, the Nasrid dynasty had made Granada its capital. Their rule stretched for more than two centuries, longer than any other Muslim dynasty in Iberia, and the Alhambra was their masterpiece. To build here was both practical and symbolic: the hill offered a defensive position, but it also set the palace apart, so that life in Granada unfolded under the gaze of the Alhambra, perched high on its rocky knoll.

In 1492, when the Catholic Monarchs entered Granada and the last Nasrid ruler, Boabdil, surrendered the keys of the city, it became the closing chapter of an age. Legend tells that Boabdil wept as he looked back one last time at the Alhambra, his mother rebuking him with the famous words: “Do not weep like a woman for what you could not defend as a man.” Whether true or not, the story captures the Alhambra’s role as both loss and longing.

Granada today carries its past as a palimpsest, each era laid over the last. In the Albaicín, Moorish courtyards, altered and adapted by generations of inhabitants, survive behind plain white walls. In churches, the traces of mosques remain — their arches refashioned, minarets turned to bell towers, and inscriptions replaced with Christian texts. Even the water still speaks in the cadence of al-Andalus — though diverted and reworked, it continues to cool, mirror, and sustain.

palimpsest noun

1. writing material (such as a parchment or tablet) used one or more times after earlier writing has been erased

2. something having usually diverse layers or aspects apparent beneath the surface

The Alhambra is the embodiment of this nexus. It is fortress, palace, garden, archive, and relic. It speaks at once of Islamic rule and Christian conquest, of splendour and neglect, of poetry and power. Its significance lies not only in what it reveals but in what it withholds.

Fortress and Dream

Cypress and pomegranate trees shade the paths as you steadily climb to the Alhambra. The gradual ascent is part of its design. It is a separation from the city and a passage into another world. At the gates, you are reminded of its first purpose: defence. The Nasrid rulers built it as a citadel, evidenced by its formidable walls and vigilant towers.

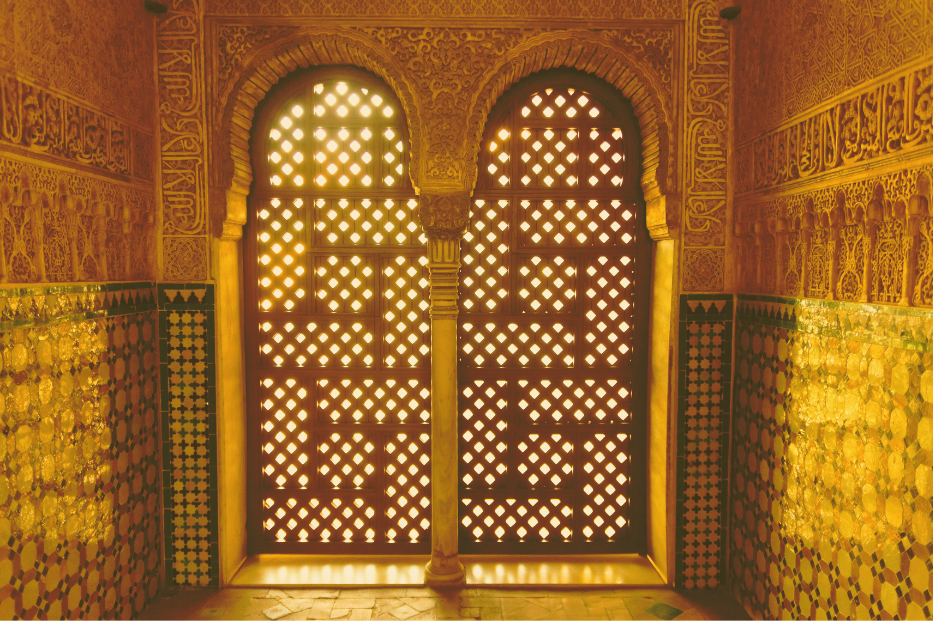

Yet, within these fortifications lies a different intention: not merely to protect, but to enchant. The Alhambra contains palaces whose interiors dissolve the sense of weight. Here, geometry is poetry, light is decoration, and water is voice.

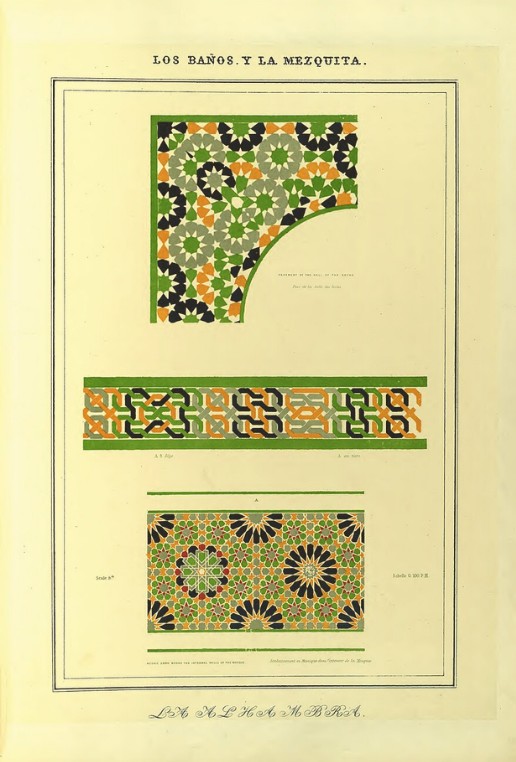

Above, the muqarnas vaults unfold in dazzling complexity — a cascading honeycomb-like structure that projects a richly elaborate interplay of light and shadow. Muqarnas examples are found throughout the Alhambra, most strikingly in the Hall of the Abencerrajes and the Hall of the Two Sisters, where ceilings fragment into thousands of facets, creating the impression of heaven contained within stone.

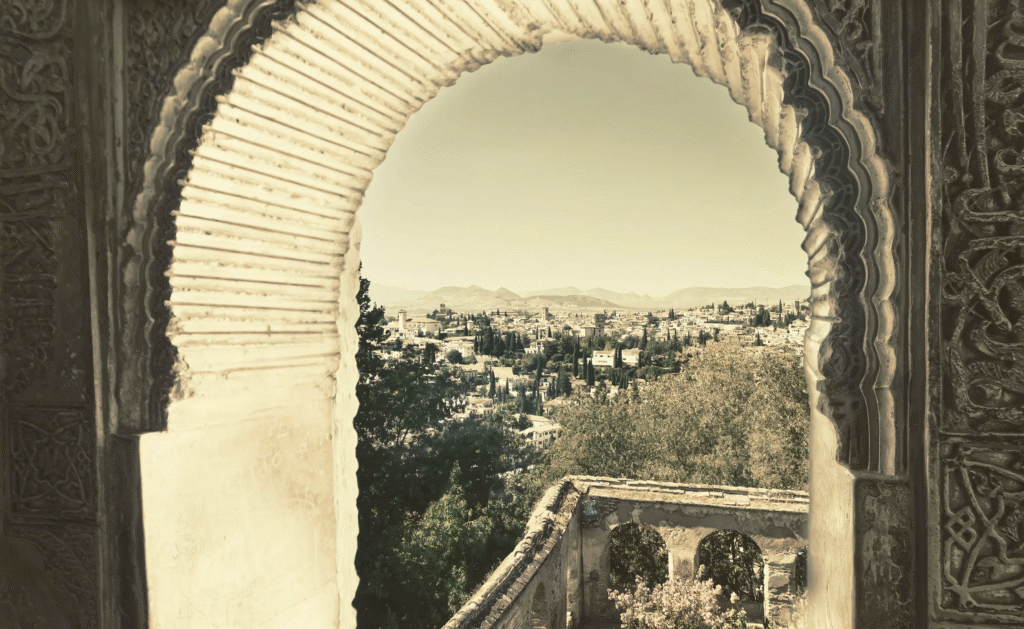

On the northern edge of the Alhambra, within the Comares Palace, stands the vast and overwhelming dome of the Hall of the Ambassadors. Set inside the Torre de Comares, the tallest tower of the fortress, it overlooks the Darro River and the Albaicín beyond. Inside, countless carved gestures form a dizzying cosmos, beneath which treaties were signed and rulers were received. It was both throne room and watchtower, a place where political ceremony unfolded under a sky of carved cedar.

In the Court of the Myrtles, a long reflective pool divides the courtyard, bordered by deep green myrtle hedges and framed by arcades. The water reflects the arches and sky above, forming a boundless still. The courtyard was the ceremonial antechamber to the Hall of the Ambassadors, designed to impress visitors with a sense of calm majesty before entering the throne room. It is a space for contemplation, where the precision of Moorish geometry finds repose in the quiet rhythm of water and light.

Water and Light

If stone gives the Alhambra its permanence, water gives it its soul. Streams course through courtyards, fountains babble and spill, and pools mirror the arches and skies above. The Generalife gardens, with their terraces and flowing rills, turn water into architecture, ordering space and setting the rhythm of movement.

This was only possible because of the Acequia Real — the Royal Canal. Ingeniously engineered, it carried water from the Darro river more than six kilometres away, using refined engineering and aqueducts to bring life to the hill. From the Acequia, water was distributed through a network of channels and cisterns, feeding fountains, irrigating gardens, and tempering the air within rooms.

“I am a garden adorned by beauty: my being will know whether you look at my beauty.

The fountain is the sultan, eternally flowing with water, bestowing without end.”

Inscriptions in Stone

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of the Alhambra is its voice. More than ten thousand inscriptions remain on its walls, arches, and domes. Some are Qur’anic verses, while others are poems by court poets praising the sultans or the palaces themselves. Together they turn the Alhambra into a manuscript: a palace written into being.

“There is no conqueror but God.”

This phrase — wa la ghalib illa Allah — is repeated throughout the complex, a refrain that is both political and devotional. Other verses describe the rooms themselves, as if the palace were conscious of its own beauty.

“Here is a cup that quenches thirst, sparkling and clear;

the hands of the stars could not fashion it so well.”

The Alhambra speaks — in praise of itself, its rulers, its God — in a voice that is equally humble and proud.

Survival and Rediscovery

After 1492, the Alhambra entered another life. Some of its palaces were taken over by Christian monarchs. Charles V of Spain even began work on a Renaissance palace within the complex in an act of both admiration and erasure, but his monument to ambition turned to abandonment in the 17th century. Other parts of the Alhambra fell into neglect, used as barracks, stables, and storehouses.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the mistreatment of the site became more overt. Under French occupation, the courts were torn up, re-laid, and repurposed, and it is uncertain how many of the Alhambra’s towers would have been obliterated, had Spanish troops not defused mines planted by the retreating French army. That the Alhambra escaped destruction and survives still today is the result of both chance and bravery.

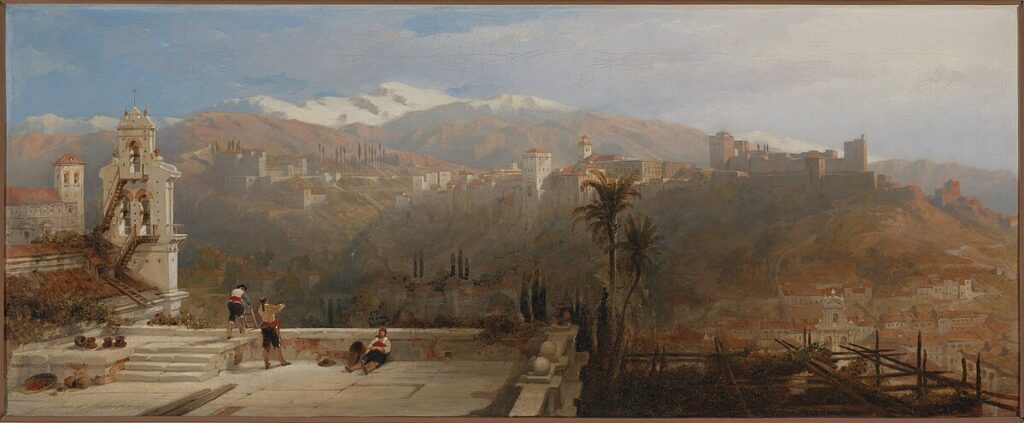

In the nineteenth century, Washington Irving lived within the complex while writing his Tales of the Alhambra, which gave it new fame and turned it into an vision of nostalgia and orientalism. Romantic artists and poets saw in it the melancholy beauty of a vanished world; half-ruined, half-preserved.

The Fortress of the Alhambra, Granada (1836), David Roberts

Today, it is one of the most visited monuments in Spain, with well over two million visitors a year. It is a paragon of endurance; yet it still carries a marked sense of vulnerability: the fragility of the stucco, the inscriptions threatened by time, and the endless repairs to cracks and breaks. Its delicacy is perhaps not believed by those gazing from the streets of Granada, where it seems eternal.

Tales of the Alhambra Washington Irving

Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra Owen Jones & Jules Goury

The Alhambra’s Meaning

The Alhambra is stone made memory. It contains the echo of a civilisation that ended but was never erased, a trace of contested coexistence, and a reminder that beauty can be born from impermanence. It represents not a single culture but the crossing of many: Arabic poetry, Islamic geometry, Christian reworking, and modern restoration.

To describe the Alhambra is always to leave something unsaid. Its patterns promise infinity, yet never contain the whole. Its surfaces resist a conclusion — just a fleeting clarity, like a reflection in a ripple.

Granada without the Alhambra would still be a city of character and layers, but with it, the city gains its axis, its sentinel, its emblem — where stone and water, power and poetry, and past and present collide.

At twilight, when lights begin to kindle in the Albaicín and the walls of the Alhambra darken into silhouette, the city seems to pause. The red castle watches as it always has, suspended between eras. In the stillness, its many histories gather into shape.

Things To Do: Exploring Granada and its Surroundings

The best time to see the Alhambra is in the early morning, when its walls glow in the pale gold of dawn, or in the evening, when the red stone deepens against the falling sky. Spring and autumn are the most temperate seasons; winter offers a dramatic snowy backdrop, and summers can be fiercely hot. Tickets must be booked well in advance through the official site, as visitor numbers are limited and entry to the Nasrid Palaces is strictly timed.

Yet, while the Alhambra is the centrepiece of Granada, there is no shortage of things to do in Granada and its surroundings.

The Mirador de San Nicolás offers the most iconic panorama of the Alhambra, especially at sunset when its walls glow red against the snow of the Sierra Nevada. For a quieter perspective, climb to San Miguel Alto, where the whole city lies at your feet.

Granada is also famous for its tapas culture, and it is one of the few Spanish cities where every drink still comes with a tapa. Try local dishes like remojón granadino (orange and cod salad), tortilla del Sacromonte (a rich omelette with offal), and the sweet piononos (a syrupy sponge cake). Many restaurants are set in cármenes — old Moorish houses with gardens that combine food with views.

Among the most important landmarks are Granada Cathedral, the first Renaissance cathedral in Spain, and the Royal Chapel, where the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castille, are buried.

Granada’s calendar is rich with festivals. On January 2nd, the Día de la Toma celebrates the surrender of the Alhambra fortress, though this festival is not without controversy. In the springtime, Semana Santa turns the streets into candlelit theatre, and in June, Corpus Christi fills the city with processions and fairs.

Granada is also a gateway to spectacular landscapes. The Sierra Nevada offers hiking in summer and skiing in winter — one of Europe’s southernmost ski resorts, where it is sometimes said you can ski in the morning and swim in the Mediterranean by afternoon. Beyond the mountains lie the Alpujarras villages, spilling down the slopes with their winding streets, terraced gardens, and quiet plazas. A short drive south takes you to the Costa Tropical, with its subtropical climate, coastal towns, and sandy beaches — one of Andalusia’s hidden seaside havens.

Some of the links in this article are affiliate links. If you buy through them, Yellow Agora may earn a small commission — at no extra cost to you.